AI: helper and perpetrator?

Enormous potential for growth. The most important of all technological innovations. More and more potential applications. Every day, we read about someone singing the praises of the colossal importance of artificial intelligence, while others greet the hype with derision and half-truths. AI has now become an established part of our day-to-day lives.

Alexa, Siri and Cortana produce answers that make a certain amount of sense and do what they are meant to do. Playlists for our streaming services, Facebook feeds and ads match our preferences, with a dose of perfect “wow!“ moments. Automated translations are good enough to allow us to understand manuals in foreign languages, while our heating systems in our cars and smart homes switch themselves on automatically. Up to now, these have all been functions aimed at everyday comfort and convenience. But if AI can do so much and still has plenty more potential, can it not help us tackle the biggest challenge facing humanity?

In view of the global climate crisis, it is striking that there is one question that is still seldom heard among the general public: How exactly do AI and sustainability fit together? What can AI do as part of protecting the climate and the environment?

Intelligent algorithms can be used to optimize almost everything from the transport of goods to the consumption of fertilizer. From forest fire warning systems to inner-city traffic management and apps to combat food waste, the range of possible applications is virtually unlimited. Both major international corporations and new start-ups are working on AI-based solutions with an appropriate measure of ambition.

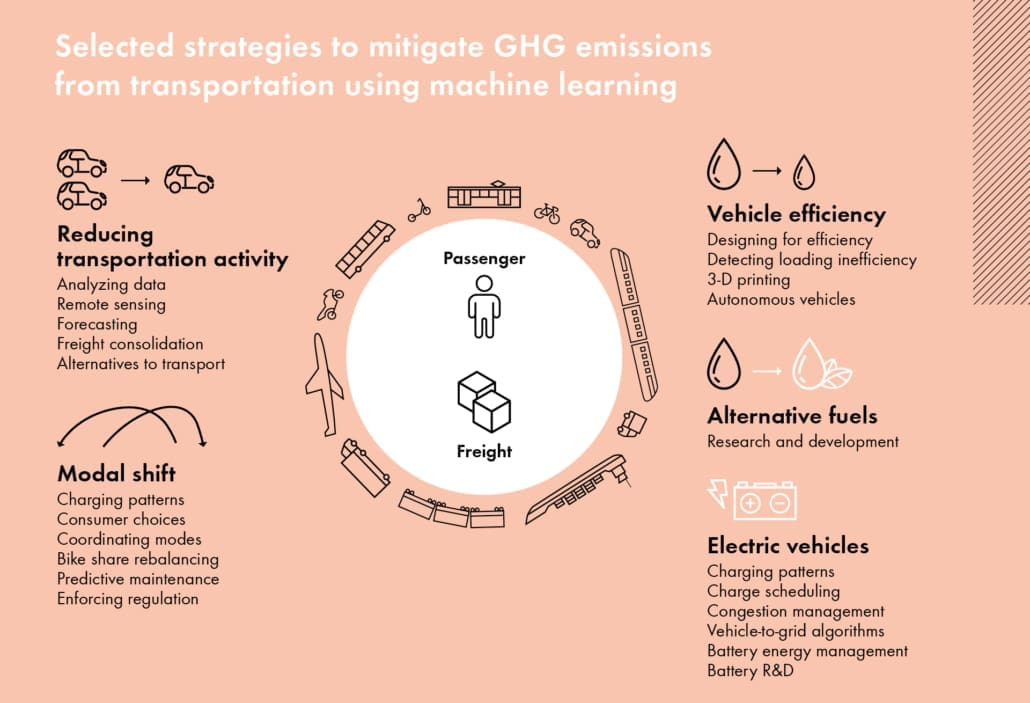

When it comes to environmental and climate protection, the situation is looking particularly promising in three areas in particular: transportation and shipping, energy and agriculture.

Short distances, perfectly interlinked chains and optimized capacity utilization for transportation and shipping

Between traffic jams, particulate matter and noise pollution, it is plain to see just how much room for improvement there is in transportation and shipping. Even getting close to achieving any climate targets requires our transportation systems to undergo a fundamental transformation.

For example, an app can automatically look for an available parking space for your car-sharing vehicle, saving many kilometers of driving over time. Research is currently under way on autonomous minibuses that adjust their routes to suit demand in real time, helping to apply a cutting-edge approach to public transit and take some of the strain off commuter routes. Combined route planning and payment for various means of transportation via smartphone are already undergoing trials in many cities. The next step is known as “intermodality.” This is the term used to refer to seamless and optimized interconnection of all transportation modes and routes, ideally taking the weather into account as well. For instance, if rain clouds are gathering, a digital travel companion will navigate its user to a shuttle bus station instead of a bike-sharing point.

Computing power can be used to prevent trucks making journeys without any cargo, while delivery vehicles can be loaded at a central location and guided in a way that ensures that there is no need for every delivery service to stop at every corner of the city. However, which services ultimately prevail is less a matter of artificial intelligence and more one of human intelligence, as well as political will.

New materials, real-time analyses and investigative talent in the energy sector

In the energy sector, which is the source of a great deal of greenhouse gas emissions, AI can provide support on a number of levels. The transition to the decentralized generation of renewable energy is almost inconceivable without it. To ensure a stable utility grid, for example, it can deliver predictions of the expected output of thousands of plants every quarter of an hour, and manage it with the aid of virtual power plants. By linking existing knowledge, experimental data and the laws of physics, AI can speed up the development of new technologies such as solar fuels and conductive materials for batteries, which can be used to store energy from renewable sources.

Environmentally damaging leaks in gas pipelines, if they do still occur, are an avoidable problem with AI. They can be detected by means of sensors or satellite monitoring and repair orders drawn up, all using automated systems. Anywhere that energy is being lost, predictive maintenance is an area of application for AI with a wealth of potential for cutting CO2 emissions.

Optimizing, calculating and monitoring in agriculture and forestry

More than a fifth of global greenhouse gas emissions are attributable to agriculture. Everyone knows about the emissions caused by cattle farming and clearing forests for grazing and arable land, but those are not the only culprits. Crop farming itself, which could theoretically be carbon-neutral, because plants store CO2, is anything but blameless for the miserable state of the climate. Plowing in serried ranks releases CO2 stored in the soil, while mineral fertilizers and deepwater rice cultivation emit nitrous oxide and methane, gases that are even more harmful to the climate. How can agriculture and forestry be made less damaging to the climate with the aid of artificial intelligence?

AI applications such as monitoring old-growth forests, wetlands and other conservation areas or automated reforestation are currently undergoing development and trials. These include functions such as calculating the ideal location, using drones to sow seeds and monitoring plant health and growth.

“Smart farming” and “precision agriculture” are synonyms for AI-assisted farming, which could be of great benefit to disadvantaged populations. FarmGrow, for example, a social enterprise established by the Rainforest Alliance and the Grameen Foundation, is supporting smallholders in the most important cocoa-producing regions of the world with the aid of smart technology.

Because the cocoa farms involved are scattered across wide areas and often in very far-flung locations, the FarmGrow advisors use remote tools to analyze the canopy and decide where their personal assistance is most urgently needed. Using satellite images, they assess the layout of the cacao trees, the shaded areas and new growth, which are both important factors in yield, and find out about deforestation. In conjunction with information from the farmers themselves regarding aspects such as their capacity to make investments as well as best practices for soil and plant health entered in the system, it is possible to draw up customized, multi-year strategies for boosting yields in environmentally friendly ways, which the cocoa farmers can call up and edit using smartphones.

The dark side of artificial intelligence

No matter how clever the AI application, how successful it is depends on training. This “machine learning,” with repeated retrieval, comparison and allocation of records from the biggest possible quantities of data, – known as “big data” – consumes an incredible amount of energy. Training an AI application in voice recognition, according to a research group from the University of Massachusetts, can generate five times as much CO2 as a car does over its entire lifetime.

To a large extent, AI applications are partially responsible for the skyrocketing global demand for computing power. Due to a lack of official data on consumption, forecasts for energy consumption in 2030 vary dramatically from 200 to 3,000 billion kilowatt-hours, while an IT study even suggests that traffic will increase but emissions will remain the same. The fact is that any AI application, even those with aimed at protecting the climate, will contribute to our high levels of energy consumption. Meanwhile, the electricity consumed is anything but green on average. What to do?

At least efficiency improves by itself

There is a glimmer of hope in market mechanisms. If a company wants to generate the most possible profit, it will ensure that the energy costs of its AI products do not exceed their budget and that its data centers are operating efficiently. Sometimes, AI can deliver the solution to its own problem, as it has done recently in Silicon Valley. Although its data center is already optimized to the nth degree, Google continued to push for several percentage points more by using algorithms to analyze processes at the data center, and did indeed manage to find more possible savings. Chipmakers such as Nvidia and Qualcomm are investing in the production of energy-efficient chipset architectures. Meanwhile, a group of data scientists aims at least to raise awareness of the CO2 impact of AI. To do so, they have uploaded a tool that can be used to calculate and disclose the carbon footprint of an AI experiment.

A calculation with many variables and quite a few unknown quantities

Wanting to use technology to conserve our finite resources makes sense only if doing so consumes fewer of them in total. That means that it will be crucial to design and use this key technology in such a way that it delivers a positive outcome overall. One thing that is already apparent is that unfortunately, there is not going to be one AI solution that we can use to close the book on the climate crisis in one fell swoop. However, what is conceivable and realistic is a mixture of many small, partial applications that, when deployed adroitly, could contribute to improving sustainability.

Artificial certainly has enormous potential to help make life better for all of us, but on one condition: we need to use it responsibly and with the common good in mind.

*Source: Rolnick, David & Donti, Priya & Kaack, Lynn & Kochanski, Kelly & Lacoste, Alexandre & Sankaran, Kris & Ross, Andrew & Milojevic-Dupont, Nikola & Jaques, Natasha & Waldman-Brown, Anna & Luccioni, Alexandra & Maharaj, Tegan & Sherwin, Evan & Mukkavilli, s. Karthik & Kording, Konrad & Gomes, Carla & Ng, Andrew & Hassabis, Demis & Platt, John & Bengio, Y.. (2019). Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning.