Always Following the Sun

From the passive House of Tomorrow by US architect George F. Keck to the Schallstadt climate houses with built-in cooling and from utopia to energy-plus buildings: a journey through 90 years of solar architecture.

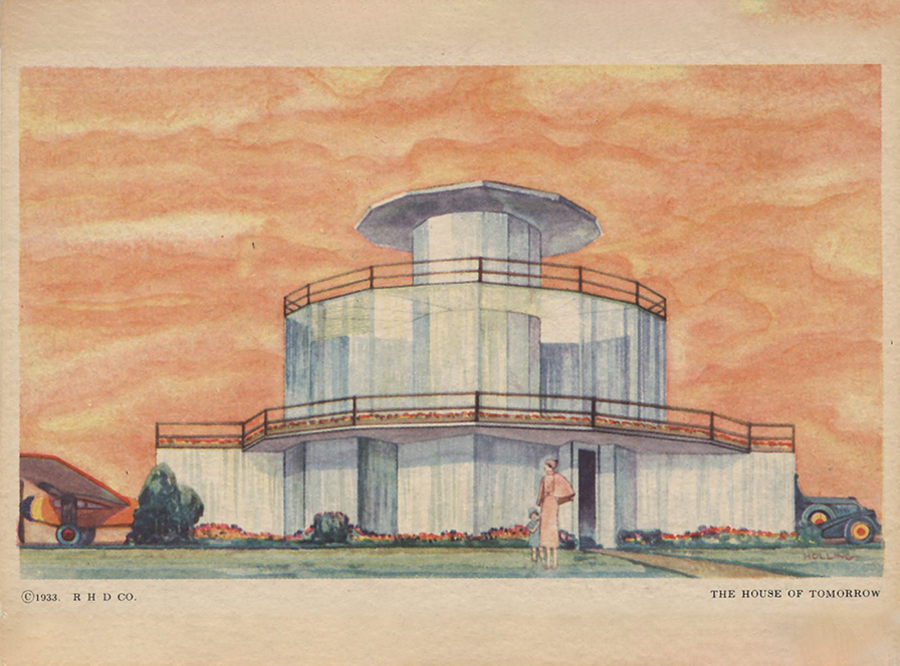

The first passive solar house was in Chicago

“This glass and steel house is circular, like three drums piled one upon another, the top drum being the solarium, surrounded by a circular roof terrace.” Visitors to the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair gazing upon architect George Fred Keck’s “House of Tomorrow” after reading its description in the brochure couldn’t help but marvel. In addition to a workshop and its own aircraft hangar complete with a replica of Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis, it also had all kinds of cutting-edge gadgets on display, such as a dishwasher and a refrigerator that could be operated without ice blocks. Keck’s House of Tomorrow was also far ahead of its time in other respects. During construction, it was discovered by chance that the glass fronts resulted in pleasant temperatures even before a heating system was installed, and thus the first passive solar house of the modern era was born. The experience that Keck gained with his House of Tomorrow led to the development of the first Thermopane multi-pane insulating glass a few years later.

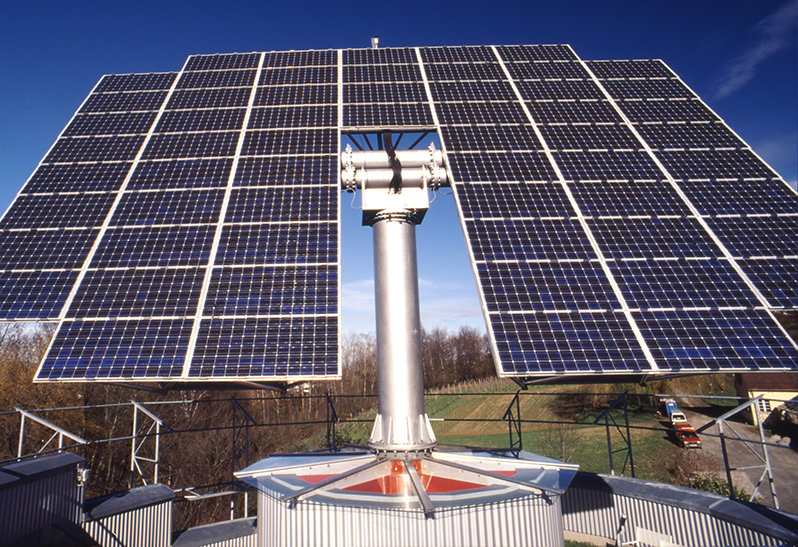

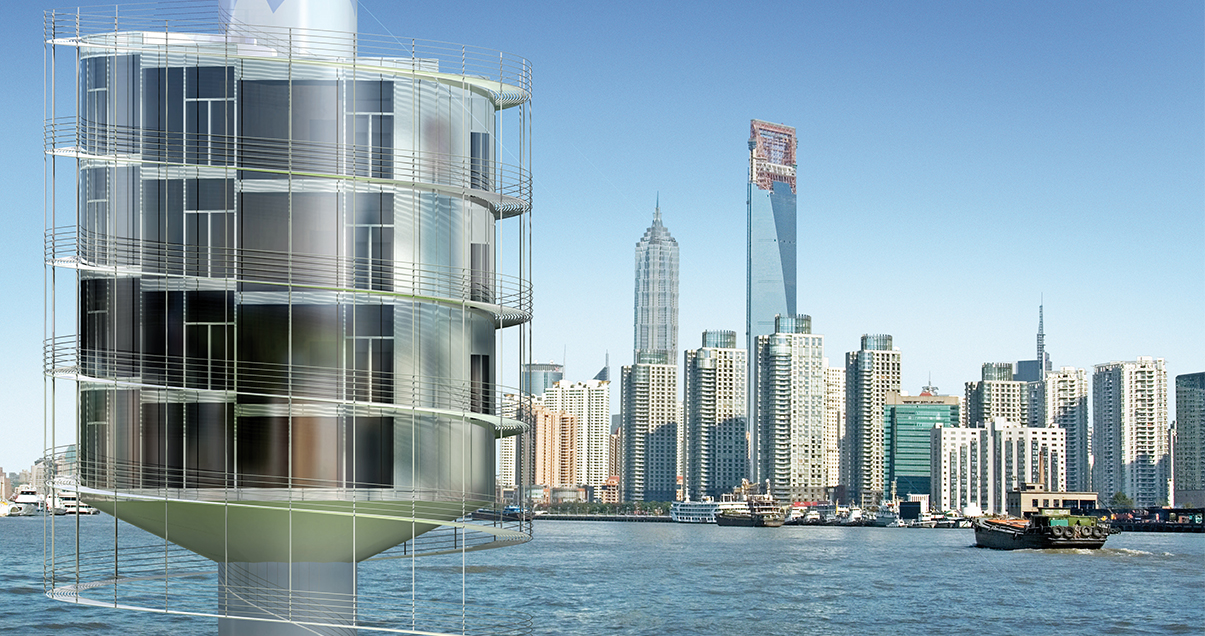

The Heliotrope solar monument

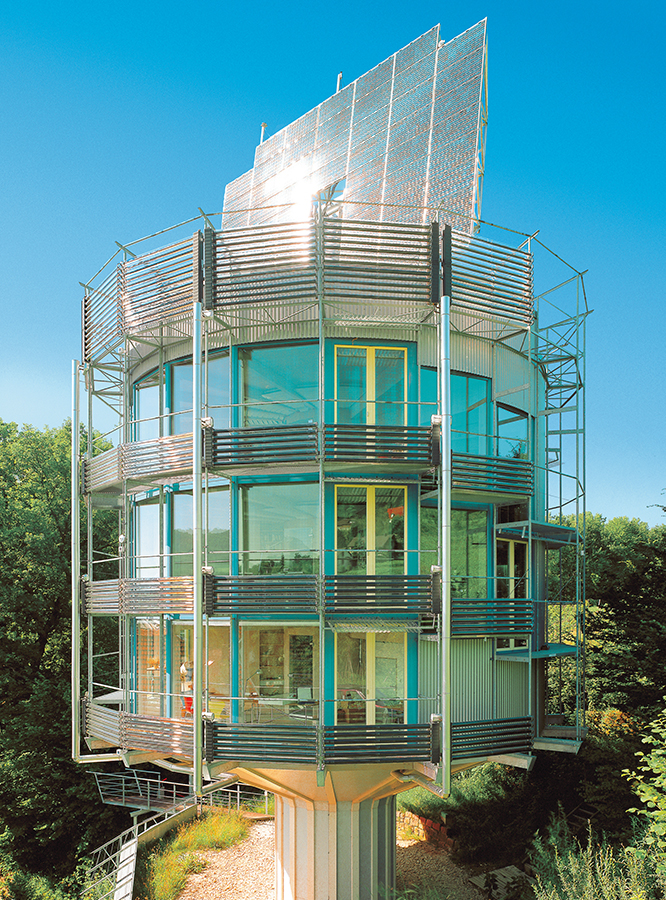

Since 1994, Freiburg-based architect Rolf Disch has lived in a revolving solar house he designed, which is cylindrical just like Keck’s House of Tomorrow. “We tried to reduce the surface area relative to the enclosed space to minimize heat loss,” he said. “A sphere would be ideal, but we’re pretty close with the cylindrical shape.”

His Heliotrope, which was recently declared a protected historic building, stands like a tree on a plot of land originally not considered suitable for development. The front of the building is glazed, while the back is thermally insulated. What makes it special is that the whole house slowly rotates on its axis. On hot days, the glass façade is turned away from the sun; on cold days, it is turned toward it to take advantage of the greenhouse effect. The photovoltaic system on the roof also adjust itself to face the sun like a sunflower. The Heliotrope was the first PlusEnergy house in the world to produce more energy than it consumes. In addition to the PV system, there are tube collectors visibly attached to the balcony railings that heat the water and the rooms. Rainwater harvesting, composting toilets and a reed bed treatment plant help make the building fully renewable, emission-free and carbon-neutral.

The core of the Heliotrope – a 14-meter-high column with a diameter of almost three meters – was planned by Rolf Disch, a trained carpenter, to be made of wood. This proved to be one of the biggest challenges. “There are lots of holes in the column for the doors to rooms, and until then there was no method at all to calculate the structural analysis. That first had to be developed by mathematicians at the University of Zurich,” recalled Disch. “The next big challenge was to find the right glue for the wood. “It needed to be just as flexible or rigid as the wood in order to withstand the lateral stresses resulting from strong winds.”

The Heliotrope has now stood on its wooden base for almost 30 years and bears witness to the beginnings of sustainable building in the 1990s. It is also the first protected historic building where the photovoltaic system is covered by the protected status.

“Far too expensive; won’t work”

For architect Rolf Disch, the Heliotrope was by no means a one-hit wonder. For EXPO 2000, his firm built the “Solar Settlement at Schlierberg” in Freiburg, comprising 59 residential buildings built from timber and with roofs made of photovoltaic modules, as well as the “Sun Ship” commercial and residential building. At the time, neither banks nor developers were willing to undertake the project. “Everyone said it was far too expensive and wouldn’t work,” said Disch. “But I wanted to know for sure, so I founded a property development company myself. We finally financed the project on the private capital market with the support of Alfred Ritter and his sister Marli Hoppe Ritter of Ritter Sport, who had faith in us.” Today, the solar-powered housing development generates around 420,000 kWh of solar power a year, and as in Utrecht’s new Cartesius neighborhood, the site remains largely car-free thanks to an underground parking garage under the “Sun Ship” office building and a well-organized car-sharing system.

Climate change reaches solar architecture

The latest project by Disch’s architectural firm – again under its own property management – is located in the municipality of Schallstadt in Baden-Württemberg. The Schallstadt climate houses are the architect’s first PlusEnergy buildings to feature built-in cooling. Quite simply, in summer, cold water flows through the underfloor heating system instead of hot water. “Ten or fifteen years ago, I would have thought that we’d have to make it work without cooling,” said project manager Dr. Tobias Bube. “But the last ten summers here have been the ten hottest since climate records began. We are in the midst of climate change and the summers are terribly hot – there is simply nothing else we can do. Heating is one thing, but cooling is also becoming more important.” The building design also allows for transportation in the form of electric bicycles and electric car-sharing to encourage residents to forgo owning cars. The underground parking garage under the building will be closed to internal combustion vehicles and reserved for electric cars and bicycles.

Showcase of an Austrian pioneer’s work

Like Disch, Austrian Georg W. Reinberg is also considered one of the pioneers of solar architecture and sustainable building in the German-speaking world. Architektur für eine solare Zukunft/Architecture for a Solar Future, a book published by Birkhäuser Verlag in 2021, provides an overview of Reinberg’s work from 2008 to 2020. “During these twelve years, much has changed in the area of ecological building,” Reinberg writes in the preface to his book. “There is now widespread awareness of ecological issues and of the looming climate catastrophe, building regulations, laws, and European programs pay increasing attention to environmental matters, and there has been some fundamental technical progress. […] As a result of this, we have been able to develop our avant-garde buildings into net plus-energy buildings, make increased use of renewable materials, develop concepts for self-sufficient urban districts, and also realize new concepts for communal living.” What is also nice about this “exciting logbook from the architect’s point of view” (publisher), with its chronological overview of projects from social housing to row houses, is that emerging problems have not been left out.

SMA supports young architects at the Solar Decathlon

In 2022, the international Solar Decathlon Europe 2021/2022 competition was held in Germany for the first time. From June 10 to 26, 18 teams of students from 11 countries presented their existing energy-efficient buildings, with energy requirements covered exclusively by solar energy, at the Solar Campus in Wuppertal. SMA provided support for the Düsseldorf MIMO team at the Solar Decathlon with expertise and a PV system. MIMO stands for the team’s working principle: “Minimal impact – maximum output.” The 40 students and nine professors of the interdisciplinary team renovated Café Ada and added a new floor to the warehouse built in 1905, earning fourth place in the competition.